In order to create the equation to solve for the Velocity Potential, we must first determine the first-order derivative of each function. Using Laplace’s Equation, we can move toward solving for the Velocity Potential.

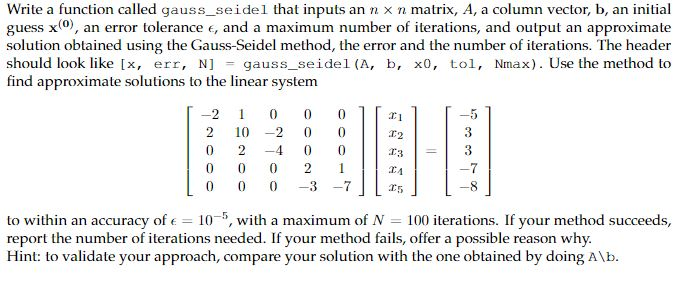

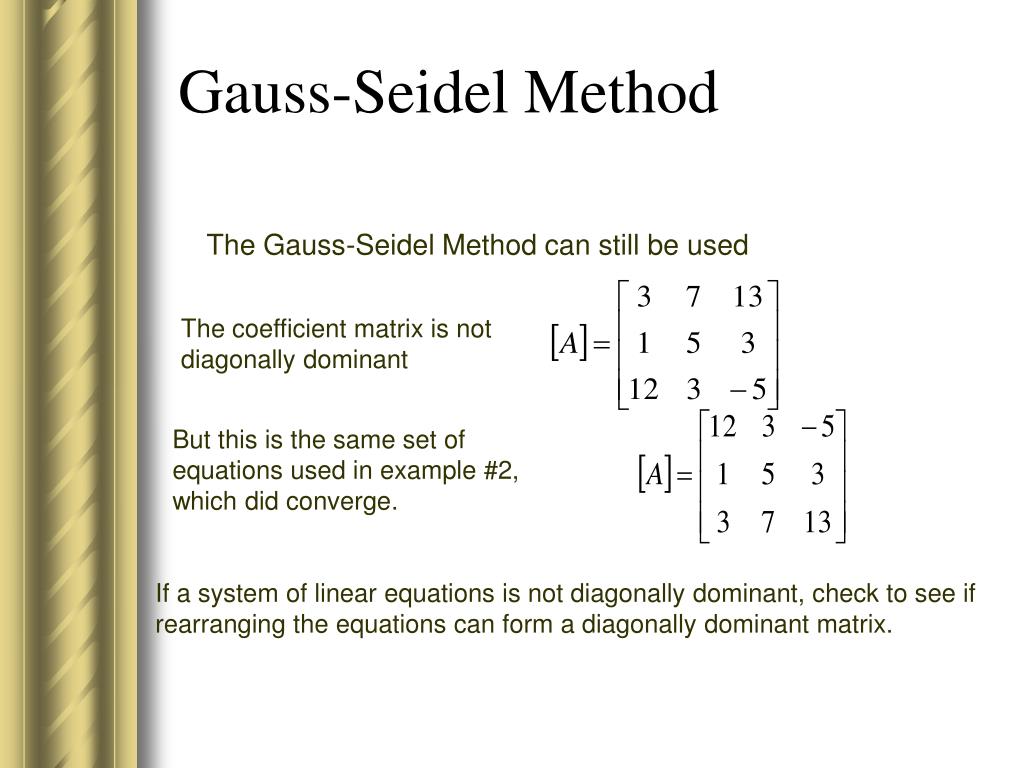

Laplace’s equation states that the sum of the second-order partial derivatives of a function, with respect to the Cartesian coordinates, equals zero: In completing research about Fluid Dynamics, I gained a better understanding about the physics behind Fluid Flow and was able to study the relationship Fluid Velocity had to Laplace’s Equation and how Velocity Potential obeys this equation under ideal conditions. I found this topic to be particularly fascinating since fluid dynamics is a type of mechanical physics that we do not have a chance to explore in our curriculum and for the simple fact that modeling invisible interactions is always a cool topic to explore. One example of this showed the application of these techniques onto devices that aid in the study of ocean surface currents and allowed for more accurate modeling of fluid dynamics. Kristy Schlueter-Kuck, a Mechanical Engineer whose research focuses on the applications of coherent pattern recognition techniques to needed fields to aid in solving a variety of problems. My interest in investigating Fluid Dynamics stemmed from a lecture given on campus in early February by Dr. I used the Gauss-Seidel Method to model velocity/electric field changes using vectors that correlate to changes in velocity/electric potential which depend on the points proximity to metal conductors/walls of pipes. My Computational Physics final project models fluid flow by relying on the analogous relationship between Electric Potential and Velocity Potential as solved through Laplace’s Equation.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)